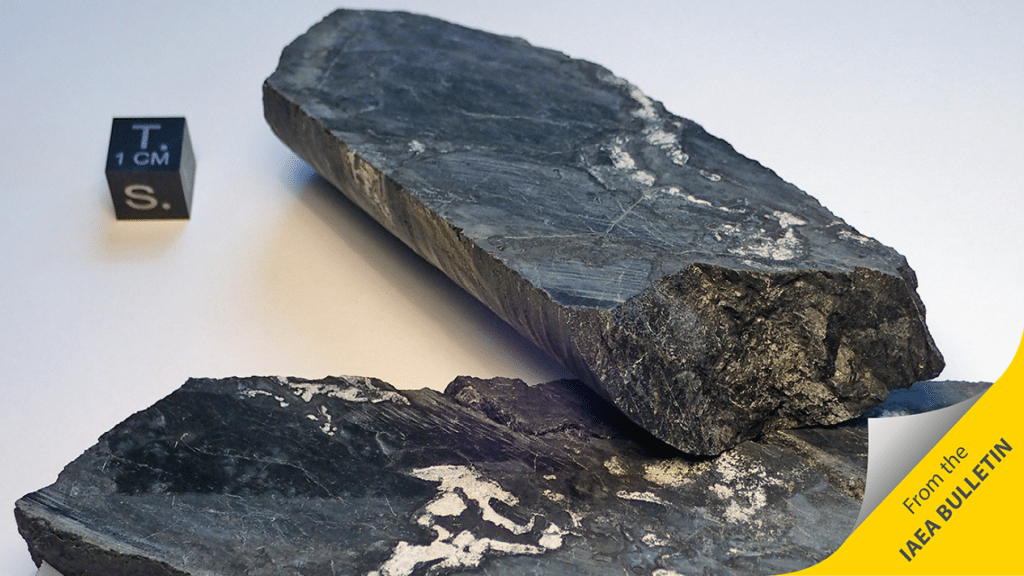

A rock sample from Oklo in Gabon, the world’s oldest and only natural reactor. Courtesy: IAEA Bulletin

Scientists appear to have unraveled the mystery of uranium ore found at a mine in Oklo region of the Central African state of Gabon that exhibits a lower proportion of uranium-235 (U-235)—the fissile sort.

According to an August 10 bulletin from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the first response that physicists had when they first found the high-grade ore in 1972 was that it wasn’t natural: “At first, all the physicists could think of was that the uranium ore had gone through artificial fission, i.e. that some of the U-235 isotopes had been forced to split in a nuclear chain reaction. This could explain why the ratio was lower than normal,” the bulletin says.

All natural uranium today contains 0.720% of U-235. “If you were to extract it from the Earth’s crust, or from rocks from the moon or in meteorites, that’s what you would find. But that bit of rock from Oklo contained only 0.717%,” the IAEA says.

Analyses of the rock by physicist Francis Perrin and his peers in the 1970s confirmed that the uranium ore was in fact completely natural. “Even more bedazzling, they discovered a footprint of fission products in the ore. The conclusion: the uranium ore was natural and had gone through fission. There was only one possible explanation—the rock was evidence of natural fission that occurred over two billion years ago.”

The IAEA posits that for such a phenomenon to occur naturally, uranium deposits in western Equatorial Africa had to have contained a critical mass of U-235 to start the reaction. For a nuclear chain reaction to happen and be maintained, it also needed a moderator—in this case, water. “Without water to slow the neutrons down, controlled fission would not have been possible. The atoms would simply not have split,” it says.

“Like in a man-made light-water nuclear reactor, the fission reactions, without anything to slow down the neutrons, to moderate them, simply stop,” said Peter Woods, team leader in charge of uranium production at the IAEA. “The water acted in Oklo as a moderator, absorbing the neutrons, controlling the chain reaction.”

Oklo’s geological context also helped. “The chemical concentrations of total uranium (including U-235) were high enough, and the individual deposits thick and large enough. And, lastly, Oklo managed to survive the passing of time. Experts suspect there may have been other such natural reactors in the world, but these must have been destroyed by geological processes, eroded away or subducted—or simply not yet found,” it says.

Oklo is the world’s only identified naturally occurring reactor. As scientists Norman Schwers and John A. Miller from Sandia National Laboratories explain in a 2017 paper, the concept of a naturally occurring reactor was originally documented in 1956 using reactor theory or the infinite multiplication constants. The Oklo reactor’s discovery in 1972 followed a routing check on enrichment by a uranium worker. “Many other papers have evaluated the Oklo phenomena and addressed issues to identify what caused that uranium deposit to go critical. Consideration of the lack of lead as a potential indicator of the age of the earth as being a possible factor. Also, the higher concentration uranium deposits (>15%) were discovered in the 1990s, and reevaluation of the overall effect on a natural criticality were not considered,” they write.

A sample of the curious rock is to be presented to the public as the central object of a permanent exhibition on natural radioactivity at the Vienna Natural History Museum from 2019 and 2020, the IAEA says.

Two rock samples recovered during drilling campaigns were donated to the museum in April 2018. The donation (and ceremony) was made possible with funding from nuclear fuel company Orano and France’s Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA). The French Permanent Mission to the UN in Vienna supported the effort.

According to the IAEA, which helped monitor radioactivity levels and handling of those samples, the two samples emit a radiation of about 40 microsieverts per hour “if you stand 5 centimetres away from them, which roughly compares to the amount of cosmic radiation a passenger would receive on an eight-hour flight from Vienna to New York.”

“We want people to learn about natural radioactivity, to make them aware of the fact that radioactivity is all around us, that it’s natural and that at low levels it’s not dangerous. Radioactivity is in the floors and walls of our homes, in the food we eat, in the air we breathe, and even in our own body,” said Ferrière. “What better way to explain this than by showing a real sample from Oklo, where nuclear fission occurred naturally billions of years ago?”

Read more: Meet Oklo, the Earth’s Two-billion-year-old only Known Natural Nuclear Reactor, IAEA Bulletin, August 10, 2018.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)

The post The Curious Case of a Two-Billion-Year-Old Nuclear Reactor appeared first on POWER Magazine.